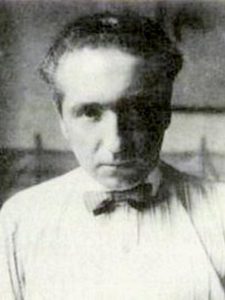

Dr. Wilhelm Reich

Wilhelm Reich (24 March 1897 – 3 November 1957) was an Austrian doctor of medicine and psychoanalyst, a member of the second generation of analysts after Sigmund Freud. The author of several influential books, most notably Character Analysis (1933), The Mass Psychology of Fascism (1933), and The Sexual Revolution (1936), Reich became known as one of the most radical figures in the history of psychiatry.

Wilhelm Reich (24 March 1897 – 3 November 1957) was an Austrian doctor of medicine and psychoanalyst, a member of the second generation of analysts after Sigmund Freud. The author of several influential books, most notably Character Analysis (1933), The Mass Psychology of Fascism (1933), and The Sexual Revolution (1936), Reich became known as one of the most radical figures in the history of psychiatry.

Reich’s work on character contributed to the development of Anna Freud’s The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence (1936), and his idea of muscular armour — the expression of the personality in the way the body moves — shaped innovations such as body psychotherapy, Gestalt therapy, bioenergetic analysis and primal therapy. His writing influenced generations of intellectuals; he coined the phrase “the sexual revolution” and according to one historian acted as its midwife. During the 1968 student uprisings in Paris and Berlin, students scrawled his name on walls and threw copies of The Mass Psychology of Fascism at police.

After graduating in medicine from the University of Vienna in 1922, Reich became deputy director of Freud’s outpatient clinic, the Vienna Ambulatorium. Described by Elizabeth Danto as a large man with a cantankerous style who managed to look scruffy and elegant at the same time, he tried to reconcile psychoanalysis with Marxism, arguing that neurosis is rooted in sexual and socio-economic conditions, and in particular in a lack of what he called “orgastic potency”. He visited patients in their homes to see how they lived, and took to the streets in a mobile clinic, promoting adolescent sexuality and the availability of contraceptives, abortion and divorce, a provocative message in Catholic Austria. He said he wanted to “attack the neurosis by its prevention rather than treatment”.

From the 1930s he became an increasingly controversial figure, and from 1932 until his death in 1957 all his work was self-published. His message of sexual liberation disturbed the psychoanalytic community and his political associates, and his vegetotherapy, in which he massaged his disrobed patients to dissolve their “muscular armour”, violated the key taboos of psychoanalysis. He moved to New York in 1939, in part to escape the Nazis, and shortly after arriving coined the term “orgone” — from “orgasm” and “organism” — for a biological energy he said he had discovered, which he said others called God. In 1940 he started building orgone accumulators, devices that his patients sat inside to harness the reputed health benefits, leading to newspaper stories about sex boxes that cured cancer.

Following two critical articles about him in The New Republic and Harper’s in 1947, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration obtained an injunction against the interstate shipment of orgone accumulators and associated literature, believing they were dealing with a “fraud of the first magnitude”. Charged with contempt in 1956 for having violated the injunction, Reich was sentenced to two years imprisonment, and that summer over six tons of his publications were burned by order of the court. He died in prison of heart failure just over a year later, days before he was due to apply for parole.

Showing the single result